Kingsley’s Head of School, Steve Farley, reflects on MLK's legacy, how parents can nurture resilience, and more.

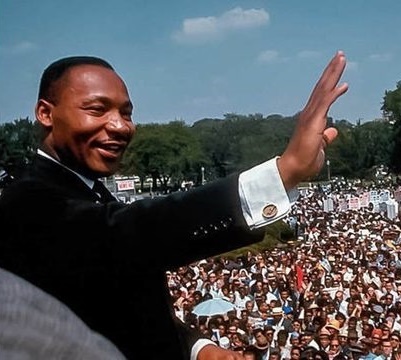

Last week, Kingsley classrooms honored Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by learning more about his civil rights activism. Do you have a favorite MLK quote or teaching?

I've been reading Jonathan Eig's recent Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, King: A Life, and what strikes me most is how central the concept of agape was to Dr. King's entire philosophy and strategy.

Agape—the Greek word for unconditional, self-giving love—wasn't just a lofty ideal for King. It was the operational framework for the movement. As Eig illustrates, King believed that agape meant loving even those who opposed you, not because they deserved it or had earned it, but because love itself was the only force powerful enough to transform hearts and dismantle systems of injustice.

What resonates with me is how radical and demanding this actually is. King wasn't asking people to simply tolerate their oppressors or be passive in the face of injustice. He was calling for active, courageous love—the kind that seeks the good of the other even while confronting wrong, that refuses to dehumanize even while demanding change.

In schools, we talk a lot about creating inclusive communities and teaching empathy. But King's commitment to agape pushes us further. It asks: Can we create spaces where children learn to love beyond comfort zones? Where they practice the hard work of seeking understanding with those who see the world differently? Where they develop the moral courage to stand against injustice while still honoring the humanity of all involved?

That's the kind of legacy worth honoring—not just in a week of lessons, but in how we build our communities every single day.

Why does Kingsley ask families to sign their re-enrollment contracts in February? Is that what other independent schools do?

Great question, and one I know can feel a bit early in the calendar year for families still settling into the rhythm of the current school year.

The short answer: Yes, February re-enrollment is fairly standard across independent schools, though timing can vary from January through early March, depending on the school.

The longer answer gets at the "why" behind the timeline. February re-enrollment allows us to have a clear picture of returning students before we make admissions decisions for new families in March. This matters for several interconnected reasons:

- Staffing and Planning: Knowing which students are returning allows us to finalize class sizes, determine staffing needs, and begin recruiting for any positions we'll need for the following year. The best teachers are often hired in January and February—waiting longer puts us at a competitive disadvantage.

- Financial Modeling: Our budget planning depends on accurate enrollment projections. February contracts give us the data we need to make informed decisions about programming, resources, and tuition assistance allocations for the year ahead.

- Fairness to Prospective Families: Families going through the admission process deserve to know whether spots are actually available. Asking for early re-enrollment commitments means we're not keeping new families in limbo while we wait to see if current families might leave.

The bottom line? This timeline reflects the complex choreography of running a school well—ensuring we can attract strong faculty, plan thoughtfully, and treat all families in the process with integrity and clarity. As always, if you have any questions about re-enrollment, please reach out to Amanda Donigan Gibbs, our Director of Admissions & Enrollment Management.

Can you remember a time when you “over-rescued” one of your kids? What happened? Why is it so hard, as parents, to step back and let children struggle?

Oh, absolutely. More times than I care to admit.

When Sam was learning to walk, I half-seriously suggested we get him a hockey helmet to protect his noggin. Sarah looked at me like I'd lost my mind. "He needs to fall," she said. "That's how he learns where his edges are." I knew she was right, but watching him wobble toward the coffee table made my heart race anyway.

Later, when both kids wanted to ride their bikes around Fenn's campus—where we literally lived, where I worked, where I could see them from multiple windows—I imagined all sorts of reasons why it wasn't safe. The campus roads. The hills. What if a delivery truck came? Sarah quickly countered my overprotectiveness with a sane response, "Steve, you're not protecting them. You're teaching them they can't trust themselves." That resonated, and she was right (as usual).

The pull to over-rescue is visceral. It's rooted in love, obviously, but it's also rooted in our own anxiety about what might go wrong. We convince ourselves we're being responsible parents when we're actually managing our own discomfort by controlling theirs.

Julie Perlow's recent piece on supporting resilient children names this tension beautifully. She writes about the need to shift from being "fixers" to helping children become their own problem-solvers. The line that stopped me: "The more we give children space to struggle, the faster they can build the skills they need to navigate school and life."

Space to struggle. That's what Sarah understood from the outset of parenting, and I had to learn. Sam needed to fall so he could learn to catch himself. Sam and Elise needed to ride those bikes so they could develop judgment about speed and terrain, and their own capabilities. And when they came home with scraped knees or hurt feelings from playground drama, they needed us to validate without immediately swooping in to fix.

Julie outlines what she calls the "Wait and See" approach for younger kids—acknowledging that friendships are fluid and most conflicts resolve themselves if we give them room. That same principle applies to physical risks, academic struggles, and all the small failures that build confidence over time.

Why is it so hard to step back? Because struggle looks like suffering when it's your child. Because we have the power to make it easier, and choosing not to feels like negligence. Because somewhere along the way, we started believing that good parenting means eliminating all obstacles instead of equipping kids to navigate them.

But here's what I've learned—from Sarah, from Julie's work, from my experience as a parent, and from decades of watching children grow: Bumps and bruises, both physical and emotional, aren't detours from development. They are development. Our job as caregivers isn't to prevent the fall. It's to be there when they get back up, dust themselves off, and decide to try again.

That's scaffolded independence. That's resilience. And that's a lot harder to provide than a hockey helmet.

And finally... it's almost the Winter Olympics! Which Winter Olympics sport do you most like to watch? Which sport would you most like to compete in?

Every four years, as the Winter Olympics roll around, my family has a cherished tradition: we gather for opening ceremonies with a dinner inspired by the host country's cuisine. It's become one of those rituals that grounds us—a reminder that the Games are as much about connection and celebration as they are about athletic excellence.

When it comes to watching, I'm drawn to the speed-on-ice events: bobsled, luge, and skeleton. There's something mesmerizing about athletes hurtling down a track at 80+ miles per hour, separated from disaster by fractions of an inch and split-second decisions. The precision, the courage, the absolute commitment required—it's breathtaking.

But here's what really gets me: in bobsled, you're not just relying on your own skill. You're trusting your teammates completely. The pilot steers, but the crew's synchronization in those explosive starts can make or break the run. It's the ultimate exercise in shared accountability and trust.

If I could compete in any Winter Olympics sport? I would want to try skeleton. Yes, it terrifies me—flying headfirst down an icy track on what's essentially a cafeteria tray. But that's exactly why. There's something about facing that kind of calculated risk, about the vulnerability of the position, that appeals to me. In leadership, we often talk about the courage to go first, to be vulnerable, to commit fully, even when we can't see around the next turn. Skeleton embodies that literally.

This has been the Kingsley Blog: Head of School Edition. Thanks for reading!

.jpg&command_2=resize&height_2=85)